Archive for the ‘Baseball’ Category

Stepping In It: Baseball’s Recent PR Blunders

I’ve worked in baseball for quite a while, and much of my work has been dedicated at least in part to public relations. At the minor league level, PR responsibilities are very different than in the major leagues. Nevertheless, I find myself at times like these shaking my head at several high-profile missteps.

The Boston Red Sox have been embroiled in a PR nightmare since their epic collapse in September. (Type the words “fried chicken and beer” into Google and the top four results are about the Sox.) And it seems with every step, they manage to find another puddle. (Disclaimer: I’ve been a Red Sox fan for nearly 30 years.)

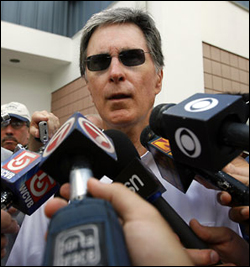

Saturday morning, one sentence from Red Sox owner John Henry gave an interview the tone of defensiveness and arrogance. When asked to explain his comments about Carl Crawford back in October, which has prompted a spring training apology from the owner, Henry said, “I don’t want to go through it again… I explained it and people seem to not want to hear the explanation.”

Saturday morning, one sentence from Red Sox owner John Henry gave an interview the tone of defensiveness and arrogance. When asked to explain his comments about Carl Crawford back in October, which has prompted a spring training apology from the owner, Henry said, “I don’t want to go through it again… I explained it and people seem to not want to hear the explanation.”

Would it have been difficult to just say, “I had a misconception about the makeup of our lineup, but our baseball operations team clarified it for me,” or even, “I stay out of baseball decisions and it was a knee-jerk opinion simply colored by the difficult month we went through”? Or he could have shown his support for Crawford by telling the press, “I think the world of Carl and we look forward to him having an excellent season.”

Instead, his answer expressed a defensive contempt for the media that journalists aren’t very fond of. Yes, we know they were digging for some more dirt and hoping Henry would put his foot in his mouth. The Red Sox owner, who is seeing the goodwill earned by two World Series titles after 86 years of pain slowly erode, effectively said to everyone, “Leave me alone!”

Pushing fans and media away with a “this is my team” attitude will alienate Henry and his partners just as much as those two championships endeared him.

Speaking of pushing people away, Josh Hamilton recently told the press, “I don’t feel like I owe the Rangers.” The comment was one of several eye-opening statements made by the former AL MVP about his stalled talks for a contract extension with the Texas Rangers.

Hamilton made headlines three weeks ago when reports surfaced that he was seen drinking at two Dallas-area establishments. For most players this is a non-story, but for a former first-overall draft pick whose substance abuse problems threatened his career, it was bound to be front-page news.

Both the content and the timing of Hamilton’s comments were suspect. He is trying to put the most recent incident behind him, but aggressively suggesting his value to the team over the last few years begs media and fans to examine both sides of the ledger. Right now, the public wants to see a humble man working hard for their favorite team. The organization needs to see a player who understands the damage his latest incident does to both Hamilton and the team, not someone trying to paint over it with past achievements.

Both the content and the timing of Hamilton’s comments were suspect. He is trying to put the most recent incident behind him, but aggressively suggesting his value to the team over the last few years begs media and fans to examine both sides of the ledger. Right now, the public wants to see a humble man working hard for their favorite team. The organization needs to see a player who understands the damage his latest incident does to both Hamilton and the team, not someone trying to paint over it with past achievements.

What is most troublesome about this is, Hamilton has an agent, so why didn’t he use him? He is going through a difficult period of his own doing, and he is embarking on a contract year. He has a person in his employ who is paid to represent him, especially when the business relationship between the player and organization is strained.

Players too often get suckered by the siren call of the microphones. They fail to realize the value of an agent isn’t always in the negotiations themselves, but in plausible deniability. An agent should be the hard-talking media magnet, the guy who takes the slings and arrows when the player’s stance might be unpopular. When the press shows up for the player’s reaction to his agent’s comments, he can draw inspiration from the clichés listed in Bull Durham: he’s just there to work hard and help the team.

Hamilton pays someone to be the bad, so let him be the bad guy.

Speaking of bad guys, no player has been more demonized in recent months than Ryan Braun. His reputation as a rising star and good guy took the hardest of hits when it was reported that he failed a drug test. The MVP award was being bestowed to a cheater, read the headlines.

The mandatory 50-game suspension was overturned, though, in a decision that crashed down on the baseball world this week. Braun arrived at spring training immediately after the announcement, holding a press conference that many have hailed as a lesson in crisis management and image recovery.

The trouble I have with it all is that the “vindication” Braun experienced is the result of a technicality. A procedural mistake got the positive test tossed out because it opened the door to either tampering with or degradation of the sample.

If this was a victory for anyone, it was for conspiracy theorists everywhere. There are those who believe Braun was let off the hook because he plays for the Milwaukee Brewers, the team formerly owned by commissioner Bud Selig. Others speculate baseball simply couldn’t handle another tarnished MVP.

If this was a victory for anyone, it was for conspiracy theorists everywhere. There are those who believe Braun was let off the hook because he plays for the Milwaukee Brewers, the team formerly owned by commissioner Bud Selig. Others speculate baseball simply couldn’t handle another tarnished MVP.

Major League Baseball, for its part, was furious. It was the first time a player successfully appealed a suspension for performing enhancing drugs. The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency called it “a gut-kick to clean athletes.”

Regardless of the arbitration result, a cloud of guilt still hangs over Braun. He continues to express that he has never taken a banned substance, but there has been no explanation as to how exogenous testosterone, or testosterone from outside his body, entered his system. His representatives did a great job of avoiding that point, because it wasn’t necessary to argue their case.

The result is a player who has been proven not guilty, but he is by no means innocent. A cloud will continue to hang over him, even as he does and says all the right things. He has no reason to revisit the issue or argue its details because he was already exonerated by baseball. The court of public opinion is not swayed by technicalities, though.

The commissioner’s office suffered a black eye that won’t heal any time soon, either. Its system was proven faulty, which will cast some doubt on any positive test, at least in the near future. The game once again has to suffer the whispers about whether one of its stars is breaking the rules. And if a perceived “good guy” like Braun can have a positive test, who else out there might as well?

This is the one case where I don’t have any PR advice except this: move on. The commissioner’s office needs to learn from its mistakes and not make them again. The press may ask about the procedure for every positive test in the next few years, and it needs to answer them politely and appropriately. It made a mistake, after all, and getting defensive like Henry will do no good whatsoever.

And Braun just needs to continue trying to be the good guy. He held his press conference, he answered the questions. Eventually, the questions will slow, though they may never stop. For his benefit, I hope he has a good season, because a drop in production will simply fuel discussion that he was an MVP-caliber player only until he was caught cheating.

But sometime soon, another player or executive will put his foot in his mouth, and my PR antennae will go up just as quickly as my fan’s heart sinks.

Johnny Damon Blew It

Johnny Damon how Sox fans remember him - if they choose to

Johnny Damon blew it.

And not by signing with the Detroit Tigers a few days ago. That was just more fallout.

No, Damon blew it in December 2005, when he agreed to sign a free agent contract with the New York Yankees.

Let me start by saying this: I’m a Boston Red Sox fan, but this isn’t a fan’s rant about how Damon turned his back on Red Sox Nation to join its most hated rival. The thought never really crossed my mind.

This is simply a practical look at a short-sighted decision made by Damon and his camp four years ago, one that will haunt him for years.

The Red Sox were a year removed from a miraculous World Series title when Damon’s four-year contract concluded. Of course, this wasn’t just any World Series championship, and in New England, it wasn’t just any miracle. This was the championship that ended “The Curse,” the victory that soothed years of heartbreak, the title that had eluded generations. That the Red Sox downed the hated Yankees in a first-of-its-kind comeback only made the win that much sweeter.

It was won by a team of personalities. Manny was being Manny, Big Papi was clutch, and Bronson Arroyo was in cornrows. Curt Schilling was forging a legend with his bloody sock when he could pull himself away from calling in to local radio shows.

Damon was one of those leading personalities. Popular in the clubhouse and the stands, his moniker for the team – “The Idiots” – was embraced by Red Sox fans everywhere. But he was more than just long hair and a caveman beard. Batting leadoff, he finished in the AL top ten in hits, walks, and runs. His two home runs, one a grand slam, helped clinch Game 7 of the ALCS and seal the history-making series against the Yankees.

Had Damon never done another thing in his life, he would have been revered in Boston and throughout New England. He could have retired on the spot and made a living doing endorsements, signing autographs, and simply being Johnny Damon.

I grew up outside Philadelphia, and I remember Tug McGraw. Tugger was a Philadelphia institution after he retired, appearing in commercials and getting a regular gig with a local TV station. He was everywhere – and Tug never even won a World Series! Imagine the life Damon would have had!

But Damon wanted to keep playing. I don’t begrudge him for that. In fact, he wanted to keep playing for a while, more than the three years the Red Sox were offering. Scott Boras, Damon’s agent, was asking for five years or more. With the Boston front office in relative disarray after the resignation of Theo Epstein, Boras wasn’t getting it. The Yankees swooped in and offered four years. What was a guy to do?

Damon did the unthinkable.

Just months after famously saying, “I could never player for the Yankees,” Damon was looking for a barber so he could conform to New York’s dress code. He said about his decision, “They [the Yankees] showed they really wanted me… I tried with Boston.” And then, in classic Damon fashion: “I wasn’t quite sure what happened.”

To a fan base where the Red Sox are religion, Damon’s desertion was blasphemous. Discussions of years and dollars did nothing to explain away the betrayal, even in this modern age of sports as a business.

Red Sox fans weren't shy when Damon returned to Fenway

When Damon returned to Fenway Park as a Yankee in May the following season, he was met with an outpouring of vitriol that only Judas would have known, had he ever played center field. Red Sox fans made it quite clear to Damon that they didn’t want him anymore, ever.

Fast forward four years to the end of his Yankee contract. Damon is richer, and he won a world series in New York. Still, I imagine he’s come to the private realization that it was nothing like the title in Boston. It was historic in that it was a championship, but it wasn’t an achievement that changed the psyche of city, if not an entire region. It’ll get him invited back for Old Timer’s Day at Yankee Stadium, but he’ll be just a role player, not a marquee attraction.

This off-season, Boras bungled Damon’s negotiations and misinterpreted the market for his client. He kept Damon in the news in all the wrong ways until the sad merry-go-round stopped with the Tigers. Detroit was “where I wanted to be, from Day 1,” said Damon. Really? I mean, really?

In watching all of this unfold, and reading Damon’s comment, I couldn’t help but think. If there were a place Damon should have always been able to return, a ballpark that always should have welcomed him, it was Fenway Park. Whether his trademark locks were flowing as he rounded third or he crept across the grass with the aid of a walker, Damon would have always been at home with Red Sox fans.

I could picture Damon throwing out first pitches for years, visiting the Sox television booth to offer absolutely nothing of substance but a smile and fond memories. He’d be doing commercials for products he couldn’t comprehend and companies he couldn’t pronounce. No one would care.

When Damon passed away, we would have wistfully recalled a season that changed anyone who experienced it. We’d have talked about the man who bestowed upon us “The Idiots.” We would have recalled a grand slam that, by then, we’d probably say actually left Yankee Stadium.

Instead, he’s just that guy who played center field before Coco Crisp. And he has no one to blame but himself.

Why You Should Care About Brendan Burke

Brendan Burke, seen here in a family photo after his father captured the Stanley cup as GM of the Anaheim Ducks.

Brendan Burke died Friday.

Never heard of him? Maybe I should rephrase it in a way that you might better recognize him.

One of six children of Brian Burke, president and general manager of the most valuable hockey franchise in the NHL, the Toronto Maple Leafs, and GM of the United States hockey team for the 2010 Winter Olympics, Brendan Burke died Friday.

For those who have heard of Brendan, you likely would have best understood this:

Brendan Burke, the openly gay son of Brian Burke, died Friday.

And unfortunately, that is what made Friday’s tragic event newsworthy.

I’ve never met Brendan, never knew him personally. Like most people, I only became aware of him when ESPN’s John Buccigross wrote a moving piece about Brendan in November.

With the Buccigross story, Brendan became a household name. His father, one of the most powerful and polarizing figures in hockey, showed his softer side. The University of Miami hockey team, led by coach Enrico Blasi, became a haven for open-mindedness and inclusion.

The article also made Brendan a question-in-waiting, namely: Will the hockey establishment be able to accept an openly gay man? Brendan was a manager of the RedHawks hockey team, but he was also planning to attend law school, with the hope of working in an NHL front office like his father.

Whether or not Brendan would have been able to craft a career in hockey will never go answered, though I’m inclined to say he would have. The issue prompts the natural follow-up, though: Would hockey, or any major league-level team sport, accept an openly gay man?

The immediate reaction to the Buccigross story on Brendan was that the NHL would accept him. Hockey, people reasoned, was more grounded and open than the other “Big Four” sports. Besides, he had Brian Burke on his side, a regular on The Hockey News list of the most powerful people in hockey.

But would an openly gay man survive as an active player in a team sport? It’s an astonishingly divisive question, if only because of the variety of answers and their rationales.

The “We Are The World” answer is, yes, of course. Sports accept athletes from all walks of life, regardless of skin tone, nationality, religion, and upbringing. That may be because at its highest levels, all that matters are results. Put on a uniform, outperform your opponents, and the sport and its fans will forgive anything from racial inconveniences to manslaughter.

Sure, such an athlete will hear it from opposing fans. But that just becomes noise to players, an energizing force whether it supports you or despises you. The media? Once again, that’s an accepted element to being an athlete.

The greatest divide for an openly gay athlete to cross will be with the players themselves. Athletes are stereotypically men’s men, explosive vessels of testosterone waiting to be unleashed upon the opposing team. But being gay is generally observed, especially among the hyper-masculine, as being less than a man. Locker room chatter is littered with derogatory comments about gays, directed towards players or actions that seem less than manly.

Jackie Robinson, left, with his Brooklyn Dodgers teammate, Pee Wee Reese.

In this respect, it’s not altogether unlike the breaking of the color barrier, the influx of athletes from Latin America, and the arrival of European players in the NHL. Negative attitudes were common and locker rooms were divided. But leaders like Pee Wee Reese, who famously put his arm around Jackie Robinson, bridged those barriers and helped make integration possible.

Buccigross wrote about a similar evolution in his article. After Brendan made it known he was gay, the University of Miami locker room changed. The players were not only accepting, but their homophobic chatter even changed. But it’s only one step to adjust locker room language. That is as much as case of being more careful about the timing or audience in which someone uses a term as it is eliminating the term from one’s vocabulary. But when the language changes, the attitude must follow.

There’s an added element to crossing the rainbow divide in team sports, though. Before a locker room becomes a place of team bonding and banter, it serves a functional purpose as a place to change clothes and shower. For players to accept a gay teammate, they have to do more than just accept him on the field or in interviews. They have to become comfortable dropping their, well, guard.

Bob Costas observed this after interviewing former NFL player Esera Tuaolo, who publicly declared that he was gay after his retirement. “It’s a hyper macho atmosphere,” Costas said. “[A] number of players expressed almost Neanderthal views about sharing a locker room with a gay person, and being a teammate with a gay person and what the consequences of that would be.”

Equally as difficult to overcome are the religious or ideological attitudes about homosexuality. The player who believes a gay teammate violates natural law or is doomed to hell might never see him as just a teammate. Players with this attitude may never see the teammate, and instead only focus on these perceived “faults.”

That there would be a gay athlete in a major team sport shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone. Studies show at least one to several percent of the population is gay; at one percent, that would make for more than three dozen at the major league level of the “Big Four” sports. John Amaechi and Billy Bean, like Tuaolo, have famously “come out” in recent years, though they did so only after their playing careers were over.

The players still became lightning rods. Former NBA guard Tim Hardaway commented that he “wouldn’t want [Amaechi] on his team.” He added, “I would… really distance myself from him because… I don’t think that’s right. And you know I don’t think he should be in the locker room while we’re in the locker room. I wouldn’t even be a part of that.”

Pat Riley, his former coach with the Miami Heat, replied, “[Hardaway’s attitude] would not be tolerated in our organization.” Riley continued, “That kind of thinking can’t be tolerated. It just can’t.”

That’s not to say that attitudes like Hardaway’s can’t change. The recently passed Bobby Bragan was one of the most outspoken members of the Brooklyn Dodgers, ardently against the arrival of Jackie Robinson and the integration of baseball. Then he watched what Robinson went through and the way he handled himself. Historian Steve Treder said Bragan “saw that he’d been wrong all along, that what he’d been taught to believe was nonsense.” He would go on to found the Bobby Bragan Youth Foundation, which every year awards scholarships to dozens of kids in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, regardless of color or creed.

What would it take for an openly gay athlete to find acceptance in a major league team sport, an environment that Costas referred to in this context as one of “hyper-heterosexuality”? Costas observed it would take “a person of guts and commitment to do it.” This thinking isn’t unlike that of Branch Rickey, who searched some time for a player to cross baseball’s color line before he found Robinson. To be more than just a token gesture, Robinson had to be the best athlete that could handle the transition, not simply the best athlete.

Still, it would require talent. Jim Bouton, author of the myth-shattering Ball Four, commented, “The first [openly] gay [MLB] player is going to have to be a good player.” Sports organizations are willing to overlook even the most grievous issues if a player can produce. They will jettison a fringe player that brings them more grief than he may be worth, though.

Bouton made a fine point when he said, “You can’t wait for every single player to accept a gay player.” In fact, 63 years after Robinson won the Rookie of the Year award, you’re likely to still find pockets of bigotry in baseball. 100% acceptance is a fantasy, a practical impossibility, be it acceptance of race, nationality, or sexual orientation. And it’s naive to expect a Bragan-like transformation of every player who opposed a gay athlete.

One fact is quite certain, though. The first openly gay player in a major team sport will always be that, before he is anything else – and he will have to come to grips with it before he ever makes the announcement. Regardless of any awards bestowed or championships won, he will always be the gay athlete that achieved them. Costas opined, in the context of sports, “[A] heterosexual person’s sexuality, generally speaking, becomes just a part of a larger persona… whereas the gay person’s sexuality becomes a definition.”

Which brings us back to Brendan Burke. The 21-year-old was by all accounts an intelligent, thoughtful, passionate man with a bright future. But on this cold Saturday, a day after his passing, we find ourselves discussing this young man not because of his past or his future, but because he was gay.

Someday, maybe someday soon, this won’t be the case.

Briefs Bits

If there were any moment that underscored the need to change the selection process for the NBA All-Star Game, it’s now. The mere possibility that Allan Iverson and Tracy McGrady could start is appalling, even if it is an event for the fans. Iverson bolted from the Memphis Grizzlies after just three games this season, landing in Philadelphia with the 76ers. Even more embarrassing is McGrady, who played in 46 minutes this season before the Houston Rockets banished him while they try to work out a trade.

If there were any moment that underscored the need to change the selection process for the NBA All-Star Game, it’s now. The mere possibility that Allan Iverson and Tracy McGrady could start is appalling, even if it is an event for the fans. Iverson bolted from the Memphis Grizzlies after just three games this season, landing in Philadelphia with the 76ers. Even more embarrassing is McGrady, who played in 46 minutes this season before the Houston Rockets banished him while they try to work out a trade.

Heralded Cuban defector Aroldis Chapman, the 21-year-old lefthander who has been clocked at 102 mph, signed a six-year, $30 million deal with the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds? Cincinnati reportedly outbid the Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Angels, among other teams. The Reds, really?

Heralded Cuban defector Aroldis Chapman, the 21-year-old lefthander who has been clocked at 102 mph, signed a six-year, $30 million deal with the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds? Cincinnati reportedly outbid the Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Angels, among other teams. The Reds, really?

If you’re ever in need of a healthy chuckle, peruse the injury reports in the NHL. In a sport where an injured player’s weaknesses can easily become targets in a battle on the boards, teams are increasingly hesitant to put a bullseye on even the most obvious injuries. Philadelphia Flyers defenseman Danny Syvret was taken into the boards recently and left the game clutching his shoulder after it was obviously separated. On the report, it’s an “upper body injury”. A player with a “lower body injury” gets knee surgery – and the injury report remains the same. My favorite is the concussion that is labeled an “upper body injury”. Expect the reports to get even more nebulous as teams approach the playoffs, too.

If you’re ever in need of a healthy chuckle, peruse the injury reports in the NHL. In a sport where an injured player’s weaknesses can easily become targets in a battle on the boards, teams are increasingly hesitant to put a bullseye on even the most obvious injuries. Philadelphia Flyers defenseman Danny Syvret was taken into the boards recently and left the game clutching his shoulder after it was obviously separated. On the report, it’s an “upper body injury”. A player with a “lower body injury” gets knee surgery – and the injury report remains the same. My favorite is the concussion that is labeled an “upper body injury”. Expect the reports to get even more nebulous as teams approach the playoffs, too.

To Dallas Cowboys fans who complain that Brett Favre and the Minnesota Vikings ran up the score with a meaningless late-game touchdown last week: “Waaaahhhhhh!” If you don’t want the other team to run up the score on you, a more effective approach might be a better defense.

To Dallas Cowboys fans who complain that Brett Favre and the Minnesota Vikings ran up the score with a meaningless late-game touchdown last week: “Waaaahhhhhh!” If you don’t want the other team to run up the score on you, a more effective approach might be a better defense.

To the Minnesota Vikings: Beware of the long collective memory shared by teams and their fans. Sometime, no matter if it’s next year or in five years, the Cowboys will exact some revenge. Of course, unless it’s a playoff game, the revenge will be meaningless, but at least Dallas will feel better.

To the Minnesota Vikings: Beware of the long collective memory shared by teams and their fans. Sometime, no matter if it’s next year or in five years, the Cowboys will exact some revenge. Of course, unless it’s a playoff game, the revenge will be meaningless, but at least Dallas will feel better.

The Colts are the Spurs, and what is the GBL thinking?

Thoughts from across the sports world, from the comfort of the couch…

It hit me after the Indianapolis Colts’ workmanlike victory over the Baltimore Ravens: The Colts are the NFL’s San Antonio Spurs of recent vintage. Consider the similarities: Championship-caliber teams that could beat you on either side of the ball. Unquestionable leaders in Peyton Manning and Tim Duncan. Strong supporting casts that recognize the value of being role players.

It hit me after the Indianapolis Colts’ workmanlike victory over the Baltimore Ravens: The Colts are the NFL’s San Antonio Spurs of recent vintage. Consider the similarities: Championship-caliber teams that could beat you on either side of the ball. Unquestionable leaders in Peyton Manning and Tim Duncan. Strong supporting casts that recognize the value of being role players.

What makes the two teams so similar, though, is the team-first attitude they both share. Players aren’t clamoring for the ball, the spotlight, or the payday. Every member plays like the success of the team rests on his shoulders, no matter how large or small his perceived role. Championships are won by everyone, and the stars eagerly step out of the limelight to share the glory. And the attitude is shared throughout the organization, instilled in each team by modest coaches who preach that when you play as a team, the result is greater than the sum of its parts.

What else makes them similar? Character. Despite the success each team has had over the last decade, they continue to avoid the trappings of modern athletes. In an era when statistics all too often count arrests along with wins, and sports headlines are littered with stories about who feels slighted and who wants more, the Colts and Spurs have remained drama-free and out of the police blotter.

What else makes them similar? Character. Despite the success each team has had over the last decade, they continue to avoid the trappings of modern athletes. In an era when statistics all too often count arrests along with wins, and sports headlines are littered with stories about who feels slighted and who wants more, the Colts and Spurs have remained drama-free and out of the police blotter.

Machinelike precision. Leadership. Character. What a refreshing concept.

Minor league baseball is well-known for creativity, and independent baseball may push that outside-the-box-but-still-on-a-budget thinking even further. Still, a recent announcement by the Golden Baseball League left me shaking my head that they may be pushing things too far – to the detriment of the league.

Minor league baseball is well-known for creativity, and independent baseball may push that outside-the-box-but-still-on-a-budget thinking even further. Still, a recent announcement by the Golden Baseball League left me shaking my head that they may be pushing things too far – to the detriment of the league.

The GBL has added teams in Maui, Hawaii, and Tijuana, Mexico, for the 2010 season, becoming the only pro baseball league with teams in three countries. But to call the GBL “far-flung” would be an understatement, especially for a level of ball that is traditionally described as a bus league. Chico, Calif., was a member of the Northern Division – where it was more than 750 miles from its nearest divisional opponent (Victoria, B.C.), and nearly 1,500 miles away from northern outposts Calgary and Edmonton. In the south, a pair of southern California locations (Orange County and Long Beach) were joined by two Arizona clubs and a team in St. George, Utah. Throw a team in Tijuana and add flight to Maui, and how does this league hope to overcome its travel costs to make any money?

In an equally curious move, the GBL has decided to abandon the designated hitter and play with National League rules. With all due respect to the DH nay-sayers, it’s hard enough to find pitchers that can wield a bat at the big-league level. To expect indy league pitchers will be able to do anything more than lay down and die is rather foolish. It might make the GBL unique (from the couch, we can’t recall another independent league that plays without the DH), but no more entertaining than regularly scheduled ritual sacrifices.

McGwire Took Steroids… Now Get Over It

Mark McGwire‘s admission Monday that he did in fact use steroids during his career was as surprising as a Milton Bradley meltdown. Some people expressed shock that McGwire, who refused to address the subject at the 2005 Congressional hearings, finally came clean. But from the couch it became apparent that St. Louis Cardinals manager Tony LaRussa must have made it a condition of McGwire’s hiring as hitting coach.

What’s curious and disconcerting all at once is the way this “revelation” has once again sparked the debate about the legitimacy of records from the steroids era – and the hypocrisy of the whole argument.

Yes, McGwire used steroids. So did Jose Canseco. And Rafael Palmeiro. And Alex Rodriguez. And Andy Pettitte. And a growing list of players from superstars to forgettables. As a result, many people argue the home run records broken in the last 12 years should be wiped from the record books. They contend Roger Maris and Hank Aaron should be returned to their rightful place, and 61 and 755 should be reinstated as hallowed numbers.

I just don’t buy it.

What bothers me most is the theory that performance-enhancing drugs are new to baseball over the last 20 years. Steroids were effectively added to the list of MLB’s banned substances in 1991 (though testing didn’t begin until 2003), but that was as a result of reports that Canseco might be juicing. Testosterone was added in 2003, HGH in 2005. The Mitchell Report went on to air baseball’s dirty laundry in some sort of sordid mea culpa in 2007.

Meanwhile, amphetamines have been a staple in baseball since the 1940’s. By all accounts, every trainer in the big leagues would toss a “greenie” to players to combat fatigue and injuries. Tired between games of a doubleheader? No problem. Out too late last night? I’ve got what you need. They weren’t even hidden, sitting in bowls in the middle of clubhouses everywhere. By the 1980’s, players could choose from clubhouse coffee with or without the amphetamines already mixed in.

And this wasn’t just a scheme for the injured or the journeymen. All-time great Willie Mays reportedly had his “red juice”, a liquid amphetamine. Hall of Famer Willie Stargell and all-star Bill Madlock were noted as the amphetamine sources in the Pittsburgh Pirates clubhouse. Even “Hit King” Pete Rose admitted he used them as well. It was widely accepted that greenies were common in the clubhouse of the legendary New York Yankees teams starring Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford, long before Jim Bouton‘s controversial book, “Ball Four”, asserted that up to half of all big league ballplayers were taking amphetamines.

The Mitchell Report did not include amphetamines, but not because baseball didn’t see the problem. The concern was that while a slim percentage of players were using enhancers like steroids and HGH, the percentage of ballplayers ingesting amphetamines would be much higher. So baseball sacrificed the few for the good of the game, and for the same reason, intentionally left greenies out of the Mitchell Report.

Arguments have been made that steroids, HGH, and the like are strength enhancers. Amphetamines, while they raise the heart rate, are more known to be “cognitive enhancers”, effectively improving the performance of the brain and upgrading focus, concentration, and reaction time. How is one group more or less extreme than the other?

Interestingly, many fans of the game will argue that it’s hardly a simple physical contest. Sure, physical tools give players more to work with, but the mental aspect of the game is at least equally important. So why are substances that improve brute force treated with such disdain, while drugs that improved mental acuity were given a pass?

If, as is being argued again following McGwire’s admission, his records should be tossed out with Bonds’, who else loses records? Does Ty Cobb become the all-time hits leader because Rose admitted using amphetamines? Are Mays’ 660 homers tossed because of his red juice? Should a full-scale investigation be initiated to determine if Mantle, Ford, Maris, or Yogi Berra were using as well? How many players on a team have to be proven to have used before that team should be forced to forfeit its World Series title?

If the players in question lose their records, who else should lose out because they too had an unfair advantage? Maybe Babe Ruth‘s home run totals should be erased, since he never had to face the talent of the Negro Leagues. Bob Feller never had to concern himself with the rigors of cross-country travel, so we’ll toss his efforts as well. Bob Gibson‘s 1.12 ERA has to go too, because he benefited from the high mound, which was such an obvious advantage that it was changed the following season. Not only were Gaylord Perry‘s records not adjusted even though he was caught cheating, but he has since been voted into the Hall of Fame – maybe now he should be tossed out.

If the arguments of the last paragraph sound a little far-fetched, then you are starting the grasp the hypocrisy of dismissing some records while allowing others. Ford Frick‘s asterisk aside, baseball performances aren’t stricken because the circumstances in which they were posted didn’t match the environment of their predecessors. The evolution of the game and the debates it prompts contribute to the beauty of the game. The irony is that even when we knew it was happening, when suspicion gave way to outright accusation, we still embraced these players and their performances.

What happened, happened. What was achieved is a part of baseball’s lore and record books. Accept it and move one… or get a mighty big – and arbitrary – eraser.